In the previous segment I have introduced the central tenets of formal Minimalism in the field of fashion. The second segment will look into its evolution, as well as the common misconception of this aesthetic.

Post-Minimalism

Like any art movement, Minimalism was bound to undergo a shift into what is broadly termed as Post-Minimalism, encompassing all the styles related to Minimalism that have branched out from the 1960s, almost right after its birth.

In the previous section, I have included Deconstructionism under the umbrella of Minimalism. Quite a number of people who read what I wrote were skeptical of the validity of Deconstruction being included in this artistic movement, often citing the complexity of the garments that do not appear to be reductive. There are two points I’d like to raise with regards to this statement. Number one, I would like to stress that reductivism is not just about creating simple geometric shapes in monochromatic tones, it is also about minimising the idea of a garment, eg. A leather jacket.

Number two, reductivism that extends beyond the aesthetics, ie out of the surface and into the design process itself, is possibly a product of Post-Minimalism, because it borders on a metaphorical stance that formal Minimalist artists were fighting against. Here is where I should probably say that Post-Minimalist ideas do include opposing ideas that are related to their parent movement.

The reason why I have included Deconstructionism in the previous segment was because the book devotes an entire chapter to it, and it makes no distinct difference between Minimalism or Post-Minimalism with regards to Deconstruction (the title In the Post-Modern Era was a big clue that I missed, it seems), and it’s only after many hours of contemplation, I came to the conclusion that there are elements of both Minimalism (repetition, exaggeration of form, extreme reductivism) and Post-Minimalism (nature of material dictating character of object) present in Deconstructionism, points which I have laid out in the previous segment.

The idea that Deconstructionism has a place in Minimalism isn’t an opinion of mine, but it’s a point that has been extracted from the book itself. To determine whether such and such movement is included in such and such field is beyond the expertise of a non-art historian such as yours truly. As a reader what I can do is to extrapolate the rationale behind its inclusion. However I can safely assume that act of its inclusion says more about the strong relationship between Deconstructionism and Minimalism rather than the former being a complete subsidiary of the latter. Now that I have laid out the most common misconception about Minimalism – that design object has to be clean and sparse – let us move on to the Post-Modern American Minimalism.

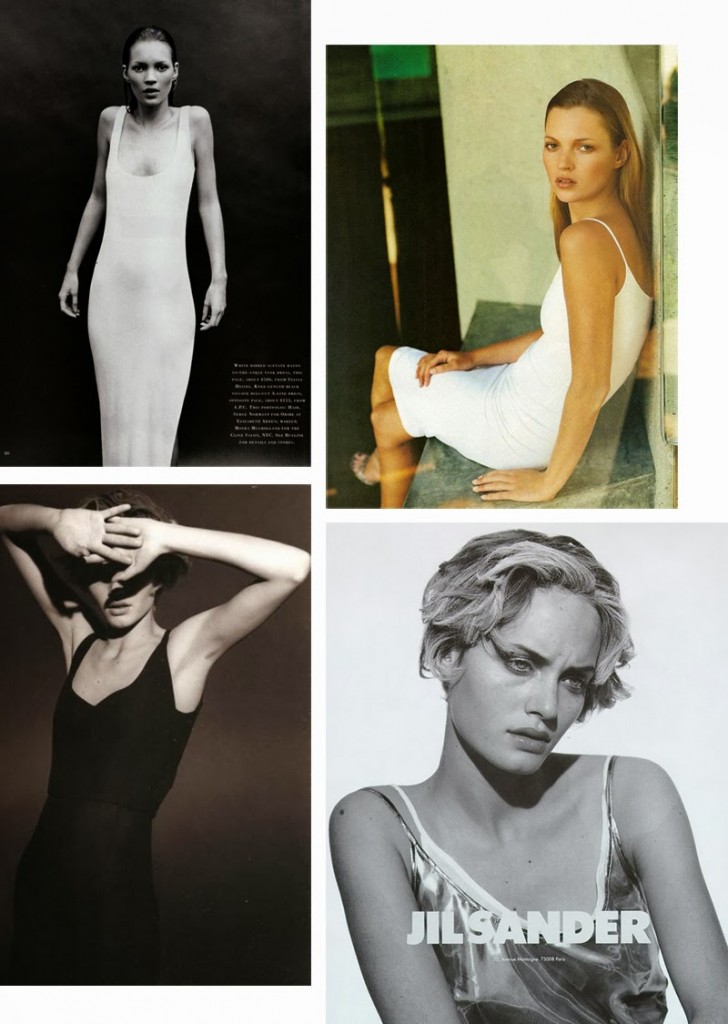

The mainstream fashion of the 90s era was marked by the shift of focus to the female arena, in which designers such as Calvin Klein and Donna Karan made easy clothes for the modern working women. Klein himself identified his version of Minimalism as ‘an indulgence in superbly executed cut, quiet plays of colour tones and clean, strong shape.’

Although formal Minimalism discouraged figuration, Post-Minimalism allows casual references to the human body, as long as they appear in reductive a manner as possible, notably exemplified by Klein’s nondescript slinky slip dresses. One can argue that Donna Karan’s and Halston’s pursuit in creating functional and portable clothing went against the anti-figuration element of formal Minimalism. It is of course not surprising because Post-Minimalism does include opposing views which I have alluded to previously.

In fact, this American brand of post-modern Minimalism was bordering on generic, so much so that it could not be separated from mass market offerings from Gap, Levi’s etc, other than through its label. In essence, the label itself became the sole compensating factor for the lack of fashion, because it was often found that the quality of the offerings did not correlate with price tags. The logo had ironically become the centerpiece, elevating mass market quality products to high-fashion level, which then begs the question: how little is too little?

A major critic of Minimalism, Michael Fried, claimed that arranging identical non-art objects in a three-dimensional field and proclaimed it art, didn’t necessarily make it so. Art is art, and object is object. In the same vein of reasoning, can one then argue that some of the so-called Minimalist fashion of the 90s, which was so easily copied by high street retailers to the point of being of lesser quality, did not deserve its Minimalist title after all? That the creativity behind the clothing was emptied, and became solely dependant on the status of the logo to elevate its value? Indeed, the question that I have been asking myself is, where do we draw the line between Minimalism, and not-Minimalism?

One can’t help but to wonder if this minimal-clothing movement – spearheaded by mostly American designers – was called Minimalism simply because it was such an easy title to attach to, also perhaps exacerbated by the stark contrast between that and the gaudy, glittery shoulder-padded Dynasty of the 80s. It was also a sharp departure from the futuristic 60s when Minimalism first emerged. Unlike the European (Helmut Lang, Margiela) and Japanese (Comme des Garcons, Issey Miyake) version of Minimalism of the 90s, instead of pursuing the purity of anti-figurative designs, the American brand of Minimalism focused the spotlight on the body more than the design object, which in this case of fashion, is the clothes. The clingy nature of the garments failed to reshape the human body but exposed the natural curves, as opposed to the artifice created a la Comme des Garcons et al.

This very literal interpretation of the word Minimalism, i.e., literally reducing clothes to almost nothing, is perhaps the reason why the term has been through so much abuse. Everything that is monochromatic and stark, even when it comes to t-shirt and jeans ensemble are now deemed Minimalist. It is also one that is most often emulated today by plenty of fashion bloggers, albeit with a slightly sporty touch à la Alexander Wang, perhaps because it is far easier to digest and reproduce.

As much as I’d like to agree with the fashion critics, I simply fail to see how we can slap the term on this aesthetic. Minimal – yes, Minimalist – not quite. On a visceral level, it feels more like a regression to a figurative approach rather than the pursuit of modernity. I do not find my intellect nor perspectives challenged with regards to these minimally-dressed bodies when I look at the seminal Calvin Klein campaigns of the 90s, in contrast to the other works that have been discussed so far. Then again this is probably a good example of post-modernism throwing its shits at any artistic movements, incorporating consumerism in just about everything it can get hold of. Having said that, I am more than happy to hear your perspective on this matter.

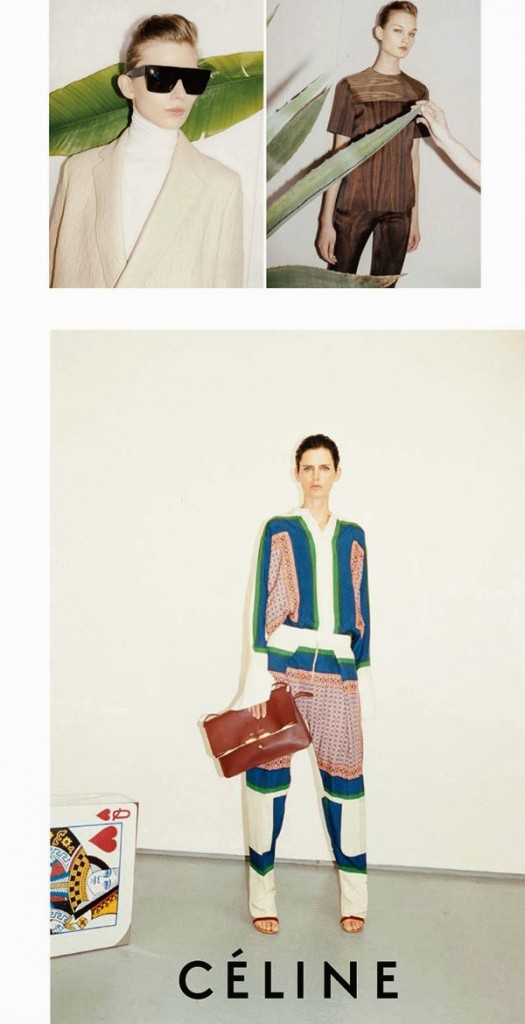

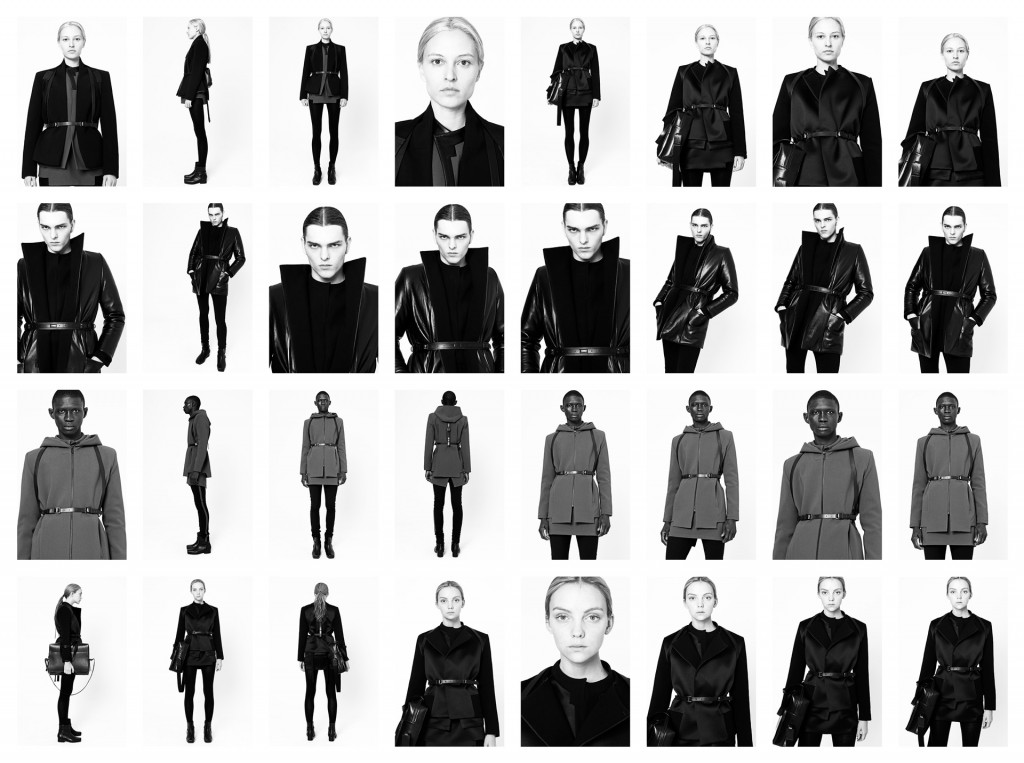

Minimalism Today

Today’s Minimalism movement in fashion continues its futuristic slant, with a stronger emphasis on geometric structures and artificiality (Gareth Pugh again). Where the old Minimalism sees the human body as a primary structure, it has now become a network of fractured places dissected by lines. There is also a stronger focus on the creation of futuristic beings, or cyborg lookalikes, inhibiting a post-gender world, continuing the conversation of removing gender out of clothing. Aesthetic still trumps function, but with an emphasis on fluidity and simplicity over intricacies (remember that Minimalism can still be intricate, it’s just that we tend to equate Minimalism with simplicity).

Ultimately Minimalism, regardless of its iterations, “seeks to challenge perception of space and matter, ensure purity of design, and to reduce form to its cogent, accessible essence.”

9 thoughts on “Defining Minimalism in Fashion: Part 2”

Lucinda

by Lucinda on September 25, 2013 at 9:48 amI think you’ve forever changed how I consider minimalism and the term itself. Like ‘monochrome’ the word has been overused until almost irrelevant and we’ve forgotten other words like spare, bare, reductive.

If you’re not already familiar with it, I can recommend the online journal Minimalissimo. Less for the objects, more for the occasional conversations and debates in the commentary.

Gracia Ventus | The Rosenrot

by Gracia Ventus | The Rosenrot on September 25, 2013 at 1:13 pmI am most definitely not acquainted with the site, thank you for the suggestion, Lucinda.

Indeed it’s so easy to just throw the word minimalist as a cop-out. Sometimes I get frustrated whenever influential sources throw the word around, and then it gets diluted even further down the line of information that I no longer know what is or isn’t Minimalism. Hence why I started exploring into the definition and decided to write these essays.

Mika

by Mika on September 28, 2013 at 12:27 pmI greatly enjoyed your series on Minimalism. Very informative! I have to admit that I dont dwell too much on the specifics and history of minimalism in fashion as I’m more familiar with minimalism in graphic design, but it’s great to see there’s an overlap with the two.

Bertrand

by Bertrand on October 5, 2013 at 5:26 amI think minimalism in design and minimalism in art are two separate phenomenon, that run in parallel but have adapted the practice to the specific requirements of their support: minimalism in art is basically the last throb of modernism, a stalwart resistance against pop art and conceptualism, an attempt at transcending frame of art by rejecting both function and meaning. Such an approach would seem impossible for design in general, and for fashion in particular, because despite regular claims to the contrary fashion (imo) is not art but is design: unlike minimalist artworks, the garments are not ‘autonomous,’ at least in the sense that

1/ they retain a function, even for the most unfunctional outfits

2/ they are sold and marketed as separates for the most part (except for the jumpsuit – an the kigu…) and are designed to provide a vocable to the customer’s self-expression.

3/ they are deeply semiotic: the very structure of the fashion industry relies on differentiation and alterity.

So to sum up, fashion can borrow an aesthetic from an the minimalist art movement but the conceptuality remain invariably unsuited : there is no ‘fashion for fashion’s sake.’

An interesting step towards an actual theory of fashion as ‘meaning-less’ has been taken by anthropologist Daniel Miller in the last couple of years, where he studies the pervasive presence of blue jeans in western society, arguing they have become ‘post-semiotic,’ in the sense that people use them when want ‘not to make a statement’ – a curious idea for sure, what do you think? As for myself I always thought that ‘raw denim’ sounded at least as modernist as ‘raw concrete’.

PS: I like your blog.

Gracia Ventus | The Rosenrot

by Gracia Ventus | The Rosenrot on October 7, 2013 at 9:10 amDear Bertrand,

Thank you for your excellent insight. Indeed I do agree that fashion isn’t art, therefore I tried my very best to always refer to fashion as objects of design when I was writing and keeping in mind that there is only so much ‘art’ one can inject into fashion.

That denim theory is certainly most interesting. Admittedly I’m not very familiar with the department of semiotics (yet!) beyond the superficial level, let alone post-semiotics. I’m not even a jeans person! But what with the pervasiveness of branded jeans, cuffed up raw denim to show off the ‘selvedge’, I’d say blue denim is still very much a social signifier. Even if a person wears a pair of non-branded, nondescript jeans, it does imply that they are making a statement in not wanting to make a statement. Almost relevant to semiotics, I shall quote David Mitchell: “My appearance should be in no way noteworthy, but then again not so unnoteworthy as to be in itself, noteworthy”.

PS. Thank you for reading my blog.

Bertrand

by Bertrand on October 7, 2013 at 5:55 pmI am not sure myself to have quite grasped the concept of ‘post-semiotic’ – and I completely agree that the denim market with its fetishizing of selvedge, of raw 15oz + fabrics and broad, conspicuous tobacco top-stitching is probably as conspicuous and spectacular as most fashion: probably the interviews on which he based his research were conducted with people with little understanding of the ‘meaning’ of denim detailing, hence the garment as a whole appeared to them as a blank canvas. I guess he focuses on the meaning gear has for the consumer/wearer, whereas you (and I!) would rather think of it in terms what it means to the designer? It’s an interesting question at any rate.

Anyway, thanks for your superb post, its lovely to read some trend analysis that goes beyond mere reporting! I will have watch Peep Show all over again to decipher their complex costume strategy haha.

Gracia Ventus | The Rosenrot

by Gracia Ventus | The Rosenrot on October 8, 2013 at 12:16 pmYes I have to agree! Thank you for bringing it up, I’m now more observant of the semiotics of clothes even on people who don’t seem to care much about fashion.

Regarding that study, it reminds me of the French scientists who concluded their study that bras are bad for women without considering MOST women wear the wrong sizes in the first place, no thanks to mainstream lingerie brands. It seems to be a common theme amongst social scientists to plunge into the subject of dress and fashion without fully considering all relevant contexts and variables.

Also here you go: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4WU5fT7Q9uw

maria laura

by maria laura on November 7, 2013 at 3:50 amI love this and the previous entry about minimalism in fashion. I think that you wrote it clearly and with a lot of formal information. I would like to now if you have some books to recommend me about this topic. I’m doing a research about this for school. congrats!

Gracia Ventus

by Gracia Ventus on November 8, 2013 at 5:51 pmHi Maria,

You can look into this book for further reading if it’s strictly on fashion: http://www.amazon.com/Less-More-Minimalism-Harriet-Walker/dp/1858945445/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1383904226&sr=1-2&keywords=minimalism+fashion