I don’t remember the last time I wrote about a trend analysis on this blog, partly because I don’t have the time to follow each micro trend, and mostly because everyone else has done a much better job at it. However there is an overarching trend which I feel very strongly about, and I thought it would be a good subject to explore for the beginning of 2015. Speaking of which, Happy New Year to one and all. I hope you’re leaving last year’s crap behind and looking forward to a better future ahead, whatever it may be. Chin up and march on.

The trend that I will be discussing on revolves around the topic of gender identity in fashion. In particular, I would like to highlight a new approach in gender ambiguity on the runway – for both men’s and women’s – that we are currently seeing in the last few seasons. And most importantly, I would like to emphasise that there is a distinction between the androgynous movement of the 20th century and the burgeoning trend that attempts to subvert the boundaries of gender binaries.

MOVING BEYOND 20TH CENTURY ANDROGYNY

The 20th century saw the rise of pseudo-androgyny in which female fashion adopted masculine associations in dress. In the 1920s, the flapper look, also known as the ‘garconne’, rose in popularity in major European cities. Women donned short bobs, and flattened their feminine curves to attain the boyish body, which was a far cry from the Victorian corset-dependent look highly sought-after just years prior. Decades later in the 1980s, women joined the boardrooms and offices. However in order to be recognised as men’s equal, they had to borrow masculine gendered symbols from them, i.e., the suit (Steel & Kidwell, 1989).

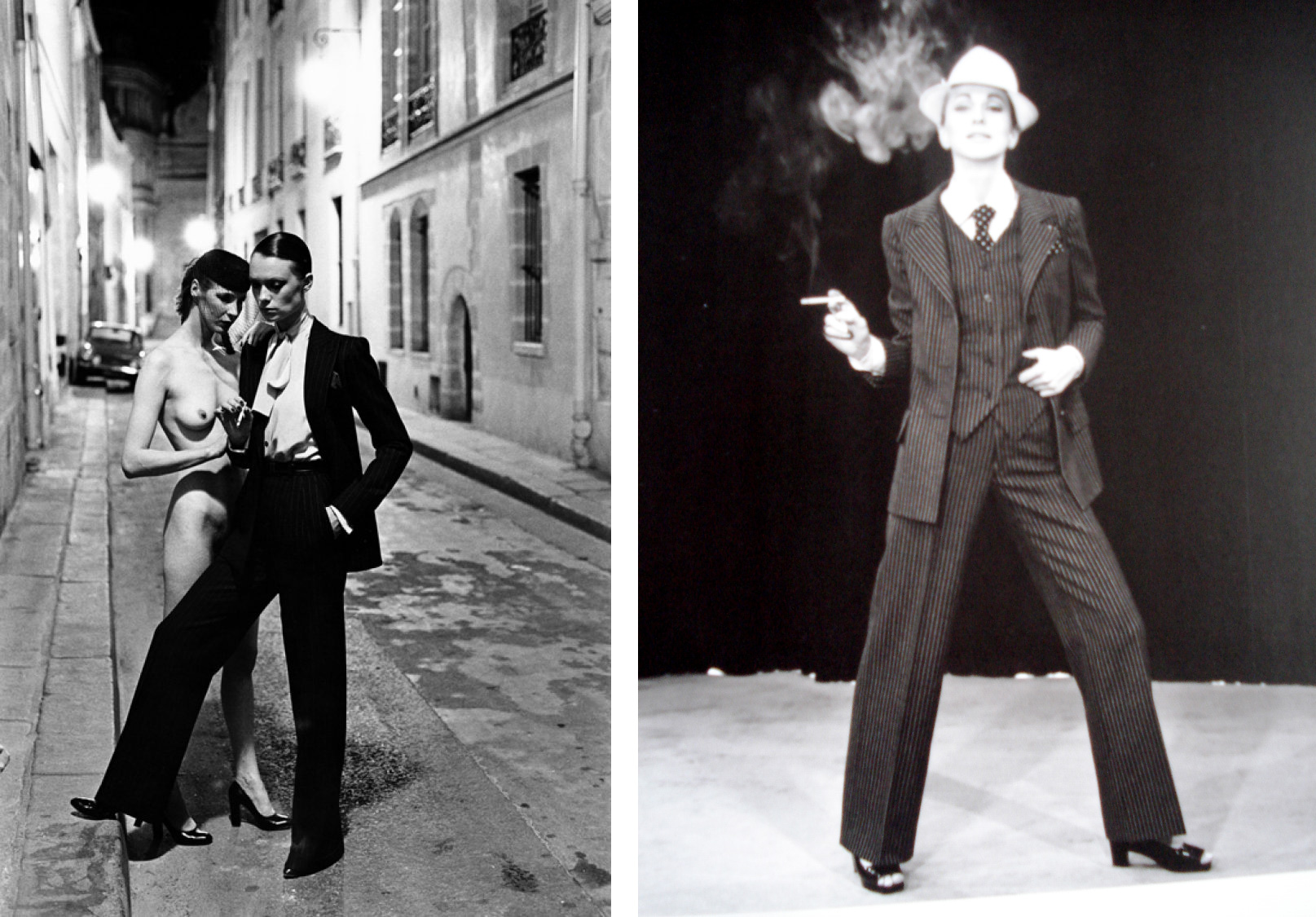

Suiting and tailoring have always belonged in the realms of masculinity, right down to the discourse on the subject (Kaiser, 2012; Yamamoto, 2011; McDowell, 1914). Yves Saint Laurent was lauded for his pseudo-androgynous smoking suit – a three piece ensemble appropriated from men’s suiting cut to fit a woman’s body. Thierry Mugler and Giorgio Armani cemented the power shoulder trend for women while ironically making bodycon, overtly sexual mini dresses for the evening, further deceiving women that true equality with men could be achieved despite a one way flow of borrowing of gendered associations – i.e., from men’s to women’s (Paoletti & Kidwell, 1989; excerpt can be found here). When feminine symbols were borrowed, such as in the cases of David Bowie and Prince, men’s masculinity and sexuality were simultaneously questioned, hence they were never widely accepted (Paoletty & Kidwell, 1989, excerpt here). It is no wonder that Enwistle (2000, pg. 169) and Paoletty & Kidwell (1989), believed that the androgynous fashion movements in the 20th century had not abolished gender distinctions as they were only playing with the boundaries of gender.

Fast forward three decades, we are seeing a vastly different approach to androgynous fashion. Unlike their staid peers, some designers have marched beyond putting women in tailored men’s clothing or conventional sportswear borrowed from the men’s. Instead, they are taking bold steps to blur the boundaries of gender binary in dress, either by removing gender marking (Rad Hourani) or creating ambiguity that subvert traditional notions of masculinity and femininity in dress (e.g., Rick Owens, Thamanyah, Craig Green, Rei Kawakubo and Haider Ackermann). By doing that, these designers are attempting to address, and even equalise the power imbalance between genders, while at the same time adopting feminine symbols for menswear, hence reversing the direction of flow of borrowed symbols, i.e., from women’s to men’s.

While one can not be too certain of the underlying reasons for this trend, I can only surmise that it is correlated with the growing interest in feminism, especially through the new media, as well as the proliferation of Minimalism on and off the runway.

Acceptance of Feminism

“They embraced their softer side — feminine, by old cultural standards — without coming across as effeminate, which marks a quantum leap for culture. This is fashion for men rid of old insecurities about gender representation. What is taking shape is, in fact, not at all an idea of fey or gay masculinity — the influence of the gay aesthetic on the heterosexual world is firmly confined to the gym-buff, clone look — but the idea that delicacy and gentleness are qualities of contemporary men worth being considered as a sign of strength, not an expression of weakness. Which, if you like, is just another ambiguity.” – Angelo Flaccavento (2014)

As feminism begins to be widely accepted in recent decades, feminine-associated activities such as fashion – which in the last few centuries had been considered frivolous and beneath men (Radway, 1987) – is now being embraced by them. More men are actively searching and consuming fashion, and are also participating in the discourse, especially via online fashion forums which seem to be dominated by men of various age groups, as can be observed on StyleForum, StyleZeitgeist, SuperFuture, and most recently, Care-Tags. Technology, through blogs and social media, exacerbates the spread of images of men peacocking in the most lavish forms of dress while attending fashion and trade shows such as Pitti Uomo (Mellery-Pratt, 2014). Such images also introduce designers who break conventional boundaries to blasé consumers, exposing them to new approaches of fashion outside of the mainstream labels.

Rise of Minimalism

It is widely believed that the most recent wave of Minimalism surfaced after the 2008 global recession, a period in which conspicuous consumption was frowned upon. Soon after, the fashion industry saw the prominent rise of Phoebe Philo and her definition of luxury – discreet yet edgy. Together with the appointment of Raf Simons – the champion of clean lines and stark silhouettes – to Dior, Minimalism became a long-term trend that has persisted to this day. One of the central tenets of Minimalism is anti-figurative forms. When applied in fashion, Minimalist dress removes the idea of a ‘figure’, negating markings of gender and sexuality frequently imbued in Western clothing. By doing so, designers can challenge conventional figurative silhouettes. Female clothing do not need to accentuate the curves while men see an increasing range of silhouettes tailored for the masculine body, previously unavailable to them, or used to be considered taboo because they were cut for the female body only. For more in-depth reading into Minimalism in fashion please refer to an older article here.

Having said that, at this point I should state explicitly the ways – there are three from my own observation – in which today’s androgyny differ from the 20th Century definition. As I have mentioned earlier, it’s no longer about women wearing suits or sportswear (which fashion journalism often reverts to), nor is it men wearing makeup and having fabulous hair.

Absence of Gender Marking

While there are indeed unisex clothing pieces in the market, such as the T-shirt, unisex aesthetic is almost always inconceivable. Designers such as Rad Hourani challenged this almost impossible task by producing collections seasons after seasons that can be shared between men and women – i.e., all the garments can be worn by both genders.

Unlike the conventional offerings of unisex clothing, which is men wearing men’s clothes and women wearing said men’s clothes to appear less feminine, his clothes de-emphasises biological differences between genders. And with the absence of gender markings, his clothes are devoid of sexuality. They are in fact almost clinical and reminiscent of cyborgs of the future.

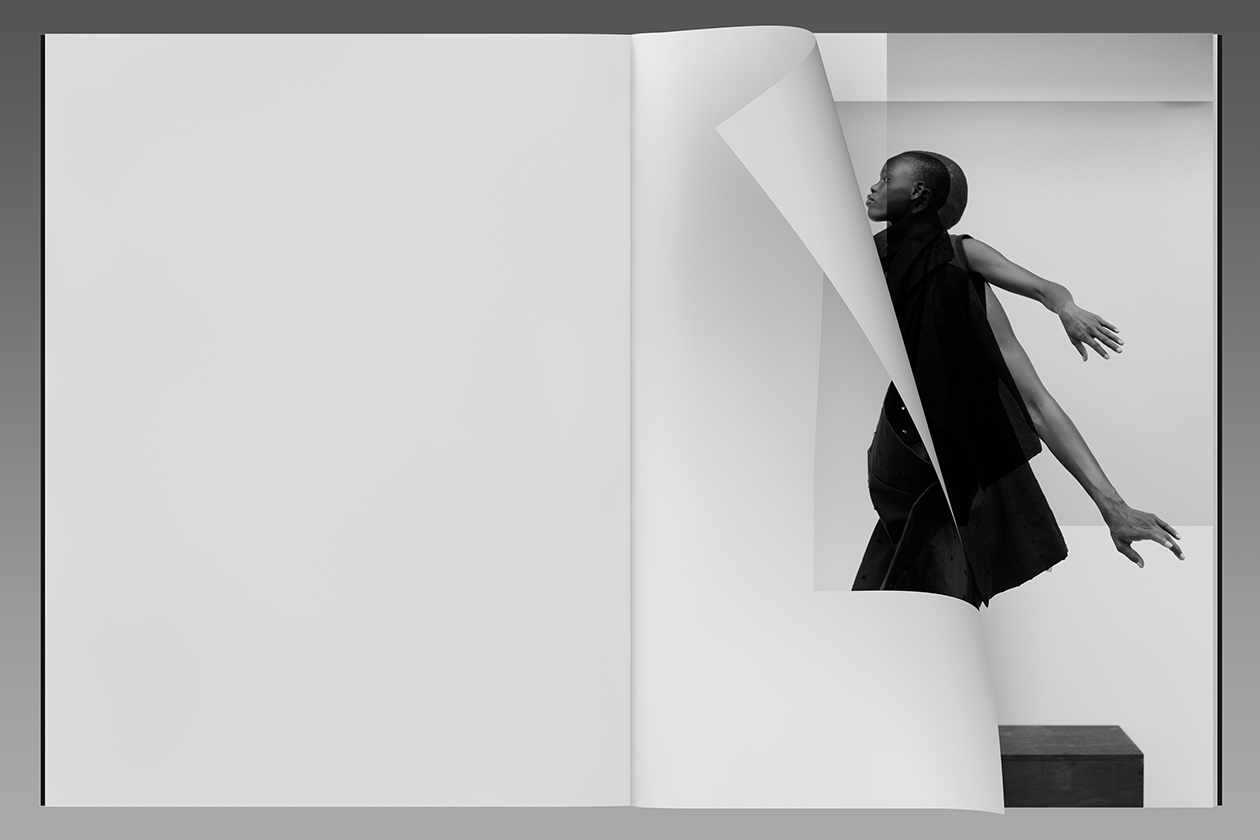

In recent times, Rick Owens has been taking the same approach with his menswear and womenswear, making unisex garments albeit with a less linear approach, which can be seen in the beginning of this essay.

Hybridity of Masculinity and Femininity in Dress

The above photograph shows a pair of ‘Pod Shorts’, a garment designed by Rick Owens. It is a bifurcated covering for the lower torso, derived from the short trousers which historically have always had strong masculine connotations. However the crotch area has been pulled to the knee level, creating a skirt-like, feminine silhouette. The result is a hybrid bifurcated garment that has ambiguous gender associations.

Soft and swaying silhouette goes against the very grain of strong and masculine modern menswear, Yet this waterfall cardigan has been made for men by various designers such as Rick Owens and Julius, and enthusiastically picked up by experimental audience. It is a garment that resembles Victorian-era robes worn by men in the privacy of their homes, but with oversized square panels that moves gracefully in motion – a characteristic usually associated with feminine womenswear.

Borrowing from Women

Male fashion is increasingly taking pointers from modern female clothing in terms of fabrication, silhouettes and colours. More designers are abandoning suitings and conventional menswear, instead preferring to explore new aesthetics by looking at and creating with what Euromodern cultures would deem as feminine elements, even if that was not the original intention of the designers. Often they are inspired by non-Western cultures which tend to have a less rigid dichotomy in dress.

For his Spring/Summer 2015 show, Craig Green showcased voluminous skirts and skirted trousers for men, cut for the masculine body while successfully avoiding sexuality-laden appearance of cross-dressing.

Rick Owens showcased the same gown made for men and women. Rick Owens first introduced this dress on his Spring/Summer 2012 show, before releasing the same dress for women in 2014, thereby reversing the flow in which fashion innovation usually occur.

The unusual lengths of the garments in the photographs above from the label Thamanyah are most commonly found in Euromodern womenswear. However these garments were actually reworks of the kandoras donned by Middle Eastern men (Pfeiffer, 2012). By introducing them to the Western audience he attempts to shake up the masculine/feminine associations of modern dress.

Moving forward

Paoletti & Kidwell (1989) stated that truly androgynous dress will eliminate the disadvantages of feminine and masculine dress, while combining their advantage. At the time of writing, historical evidence points towards an acceptance for women to adopt masculine symbols, but not the other way round. Fortunately, the current crop of influential designers are slowly changing the way we view gender and sexuality in dress and the consumption of fashion.

Wilson (1985, pg. 228) postulates that fashion acts as a vehicle for fantasy. If that is true, perhaps the persistent trend of blurring and erasing gender boundaries represents a dream for a feminist utopia, in which people of all gender spectrums, social and cultural backgrounds are recognised for their differences but not treated differently.